This is a guest post by Caroline Wood of the Ingredients in Business out of Canberra, Australia.

There are lots of pieces you have to put together to get your pricing right for your food products; knowing where you fit in the market, what your competitors are doing and of course covering your costs. You may be tearing your hair out putting all these elements together to make a profit, especially as they all interact.

A classic example of this interaction is your breakeven point. That is the point where you are selling enough at the right price to cover your costs. That whole mix of covering your costs and making a profit while not pricing too high that you don’t sell anything.

But How Do You Work Out Your Breakeven Point?

The first step is to work out the cost of making your food product. The way many food business owners do this is to work out what is called the cost of goods sold which is the ingredients, packaging and the cost of their time or staff. Then they add on a margin, a percentage to cover all the extra costs of running their business; think insurance, kitchen hire, paying for a market stall, wastage, advertising and the list goes on – all their overheads.

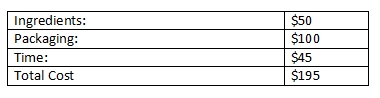

Let’s look at an example. We make 100 bottles of hot sauce and the cost of goods sold is:

That’s a cost of $1.95 per bottle. But it doesn’t include those overheads, so a margin is added. The margin varies depending on what you are selling and the market you are selling in but for the purpose of this example let’s say you set your margin at 40%.

To work out your minimum selling price you would divide the 1.95 by 1 minus the margin:

$1.95 / (1 – 0.4) = $3.25

This would mean you have $3.25 less $1.95 = $1.30 per bottle to cover your overheads.

And it is great to know this but it doesn’t guarantee you will make a profit. If it costs you $1,000 a month in those pesky overheads then if you only sell 100 bottles you will only make $130 to cover those overheads. You are making a loss. Which is fine if you are making your sauce as a hobby but not as a business, and it certainly doesn’t compensate you for the risks you take as a business owner.

To cover your overheads, you would need to sell $1000 divided by $1.30, 770 bottles.

When you sell more than 770 bottles you start to make a profit. If you sell 2,000 bottles, then you are going to make a profit of $1,600. Of course, that assumes your overheads don’t go up with each bottle (which is probably not strictly true), but you get the idea.

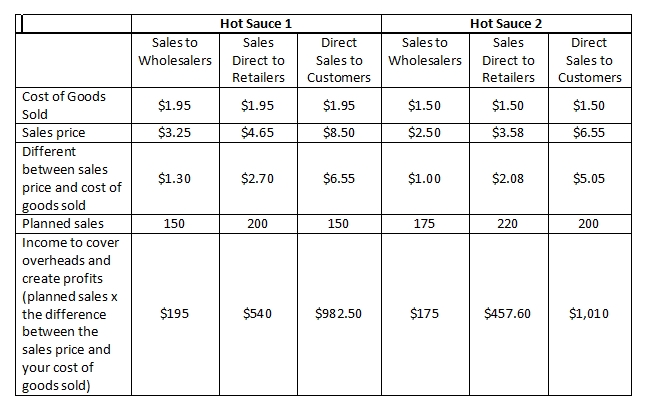

It gets more complicated when you add in more products or have different prices. The price above is the one that you ideally want to use to sell to wholesalers, who will then add on their margin to cover their costs in selling and distributing to retailers plus a profit and then retailers will then add on their margin to get the price they sell to customers.

If you are selling direct to retailers you will ideally charge the price that the wholesaler will sell to the retailer, and you would use the retailer’s price for selling direct whether that be online or at markets. If in our example the retail price for your product in stores is $8.50 and you sell at the market for that same price then you could be making $6.55 to cover your overheads and make a profit ($8.50 less your $1.95 cost of goods sold).

If you are selling direct at $8.50 you would only need to sell 153 bottles to cover your overheads ($1,000 in overheads divided by $6.55).

I know some people feel they should set a lower price when they are selling direct because they aren’t incurring any additional costs but people are often willing to pay a premium at markets. They get to meet the producer, it feels more like a handmade product when compared with something bought off of a supermarket shelf and you can interact with your customers, giving them taste tests, explain the quality of your ingredients and showing them how to use your product.

Plus you don’t want to undercut your retailers – they can get a bit annoyed at this.

If you never intend to sell through wholesalers or retailers then you have more wiggle room with your pricing but for most businesses that probably means you won’t achieve large volumes and those fabulous big profits. Which is more than fine if you can achieve your goals this way, with the key word being your (and not what everyone else says should be your goals).

How to manage all of this? As a minimum I suggest setting up a table like below that you can at least track against and have goals to meet in terms of sales:

If you add up the bottom row of the sheet you have $3,360.10 to cover overheads and make a profit. Work out what those overheads are and make sure as a minimum they are covered by the $3,360.10. If your overheads are more than the $3,360.10 then you have 4 options (aside from the making a loss option):

- Make some cost savings. If people think your product is overpriced and that is why they aren’t buying in the volumes you need to make a profit then look at ways you can save, or delay some costs until you are selling more but you don’t want to compromise on your product, particularly if you are selling it as a premium product.

- Sell more bottles – you need to have a plan for this and make sure any additional costs you incur through marketing are covered by the additional sales.

- Put up prices – but will this impact on the number of bottles you sell? Can you make slightly smaller bottles that are cheaper to make but sell them at the same price without upsetting your customers?

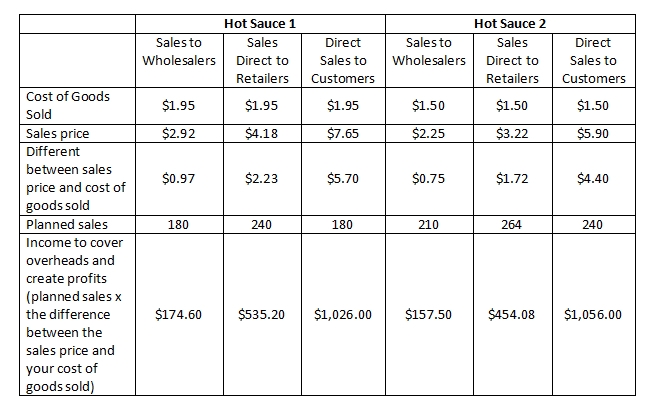

- Sell more bottles at a lower price – the table below sets out what would happen if you cut your prices by 10% but increased sales by 20%.

This time around we have $3,403.28, not a huge increase (an extra $43.18) but it may be just enough to cover your costs. Again you need to make sure you are going to sell enough extra bottles to cover your overheads given the reduction in your profit margin per bottle.

Pricing Is an Art and a Science

The key to pricing is that while there is some underlying science it is also an art to find what works with your customers. While you can ask your customers, it is unlikely they will ever tell you that you should put your prices up and they may say that they will buy three bottles if you do a buy four get one free deal . But when the time comes will they actually open their wallets?

The only way to really work this out is by doing some testing. Go the markets and have a sale or do a deal like buy four get one free to see what happens. If you are looking at higher prices, do a trial at a market that is not your main income source. After a bit of testing you will start to get a sense as to what your price should be for you and your customer.

Have you done testing? What worked for you in getting your prices right?

Caroline is a foodie accountant who specializes in helping foodie entrepreneurs to scale up and grow at the Ingredients of Business . She combines her food knowledge from being a catering officer in the Air Force with the business skills gained from working as an accountant.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks